The Inverted Pyramid: What Bertrand Russell Can Teach Us About The Limits of Logic

“To refute the solipsist…all that you have to do is take him out and throw a rock at his head: if he ducks he’s a liar. His logic may be airtight but his argument, far from revealing the delusions of the living experience, only exposes the limitations of logic.” – Edward Abbey

Something in Betrand Russell’s a History of Western Philosophy caught my eye recently. At first I noticed it because it’s basically Russell badly dissing another philosopher. But after I thought about it more I realized his point is really relevant to the way we think about the world and the way we make decisions.

In the passage that I’ll quote Russell wants to outline the differences between analytic and continental philosophy.

It’s difficult to define the exact differences between the two schools (they’re both terms that encompasses lots of different philosophers and world-views) but, roughly, analytic philosophy tends to try to break down philosophical problems into tiny pieces (like the definitions of words) and take a careful and considered look at each of the pieces and their relation to one another. Continental philosophy, on the other hand, is a bit more literary – it’s less concerned with the definitions of words and more concerned with broad synthesis.[^1]

Here’s how Lord Russell talks about the distinction:

“There is first of all a difference of method. [Analytic] philosophy is more detailed and piecemeal than that of the Continent; when it allows itself some general principle, it sets to work to prove it inductively by examining its various applications.”

By this he means that analytic philosophers don’t generally talk about broad, general principles. Instead, they like to build up their world-view in a more piecemeal fashion – considering one little question at a time. And when they do accept some general principle as true, they do so only when they can prove it by considering lots of empirical evidence in favor of the fact that it is true. They try not to make any large logical leaps that aren’t backed by experience.

By contrast, he says, Continental philosophers prefer deduction from first principles. As an example he talks about Gottfried Leibniz – the man who invented calculus[^2].

He chooses to examine how Leibniz argues for monadology – which is a theory of the nature of matter. The basic gist is that matter is made up of infinitely many “monads” – somewhat similar to geometrical points in that, by themselves, they don’t have “extension” or mass but when you get a lot of them together you can get a substance like wood or metal or dirt.

Lord Russell writes:

“When Leibniz wants to establish his monadology, he argues, roughly as follows: Whatever is complex must be composed of simple parts; what is simple cannot be extended[^3]; therefore everything is composed of parts having no extension. But what is extended is not matter. Therefore the ultimate constituents of things are not material, and, if not material, then mental. Consequently a table is really a colony of souls.”

Whoa! What just happened here? It seems like we went from some very simple basic propositions to an outlandish conclusion: “A table is really a colony of souls.”[^4]

How did that happen? Russell answers:

“The difference of method, here, may be characterized as follows: In Locke or Hume [both of whom are analytic philosophers], a comparatively modest conclusion is drawn from a broad survey of many facts, whereas in Leibniz a vast edifice of deduction is pyramided upon a pin-point of logical principle. In Leibniz, if the principle is completely true and the deductions are entirely valid, all is well; but the structure is unstable, and the slightest flaw anywhere brings it down to ruins. In Locke or Hume, on the contrary, the base of the pyramid is on the solid ground of observed fact, and the pyramid tapers upward, not downard; consequently the equilibrium is stable, and a flaw here or there can be rectified without total disaster.”

Russell’s problem with Continental philosophers is that they start with an axiomatic principle – something like “Whatever is complex must be composed of simple parts” – and they use it to deduct the rest of their worldview.

This is actually a valid method of figuring things out. For example, Euclid’s entire system of geometry is deducted from a few axiomatic principles. Pretty much any mathematical system works like this.

But what Russell is saying is that this system of thinking, while incredibly powerful, is also incredibly brittle.

This is generally not bad when you’re dealing with something like math because it doesn’t have to comport with experience – the axioms are true because we say they are. But when you’re reasoning about the real world it becomes a huge problem: it’s often impossible to tell if your axioms are correct. And equally difficult to know whether each of your deductions are valid.

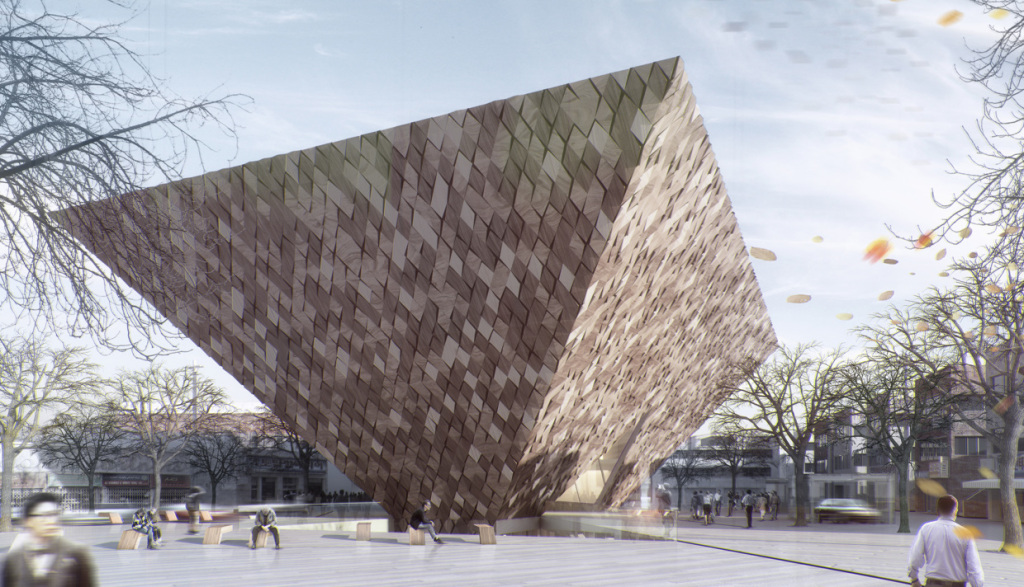

And, if you’re reasoning in this way, if your starting axioms are wrong, or any of your deductions are invalid, all of your conclusions are totally wrong. It’s not robust to error at all. It’s a system of thought built like an upside down pyramid – the whole thing rests on one single point of balance.

Russell argues that a better way to do philosophy (or figure things out about the world in general) is to construct your pyramid right-side up. Start with known, observed facts about the world and construct your argument based on those. This will allow you to build a base of thought with strong foundations; one that’s much more robust to small errors than a purely deductive system of thought because it won’t come crashing down if one little piece is wrong.

There’s a common expression among programmers that goes, “Garbage in, garbage out.” And this is exactly how logic works. It’s a powerful tool that’s only as good as the person that uses it. And when we’re reasoning about things in the real world we want our system of thought to be like a right-side up pyramid – logic based on a robust foundation of experience – rather than a long chain of deduction that’s vulnerable to error and easy to tip over.

[^1]: If this still seems hopelessly unclear that’s because it is. To actually understand the differences you need to read some of the philosophers in question.

[^2]: he and Newton both independently came up with it around the same time

[^3]: Again this means, roughly, that it doesn’t have mass

[^4]: There’s a question about whether Bertie is really being fair to Leibniz here, but we’ll let it slide to hammer home the point.

Recent Posts