Charlie Munger On How To Build A $2 Trillion Startup

Imagine it’s January of 1884 in Atlanta, Georgia. Glotz, an affluent fellow citizen, has invited you to participate in a peculiar competition:

You and twenty others are invited to present a plan to start a business that will turn a $2 million investment into a business worth $2 trillion by the year 2034.

Glotz will personally give $2 million to the person who presents the most compelling pitch in exchange for half of the equity in the new venture. There are only a few stipulations:

- The new venture must exclusively sell beverages (specifically non-alcohol or “soft” beverages)

- For reasons unknown Glotz has decided that company must be named Coca-Cola

You have 15 minutes. What would you say in your pitch?

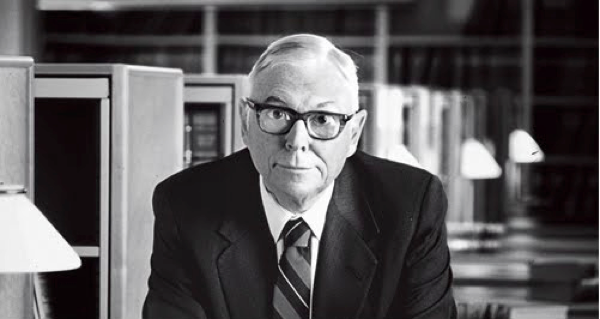

That’s the question that billionaire Coca-Cola investor Charlie Munger posed to an audience at a talk in July of 1996.

What followed over the following few minutes was an entrancing exhibition of multi-disciplinary wisdom and business acumen. Munger’s main point is that the most complex questions often have basic answers rooted in elementary academic wisdom (mathematics, psychology, etc.) He wants to show that applying some of these ideas regularly can help us to better explain business success, and make better decisions.

To start his talk, Munger lays out five principles he will use in his pitch to Glotz:

- Decide big no-brainer questions first

- Use math to help explain the world

- Think through problems in reverse

- The best wisdom is elementary academic wisdom

- Big (lollapalooza) results only come from a large combination of factors

Munger then dives in to solving the problem with his first principle: the big no-brainer questions that can be answered first.

“Well, Glotz, the big “no-brainer” decisions that, to simplify our problem, should be made first are as follows: First, we are never going to create something worth $2 trillion by selling some generic beverage. Therefore, we must make your name, “Coca-Cola,” into a strong, legally protected trademark. Second, we can get to $2 trillion only by starting in Atlanta, then succeeding in the rest of the United States, then rapidly succeeding with our new beverage all over the world. This will require developing a product having universal appeal because it harnesses powerful elemental forces. And the right place to find such powerful elemental forces is in the subject matter of elementary academic courses.”

Off the bat, it’s interesting to note how his prescription for growth largely mirrors the conventional startup wisdom espoused by Peter Thiel and others: grow quickly in a small market that you can dominate and then expand from there.

In the case of software, that market is typically a small niche of consumers. In the case of Coca-Cola (especially in the 1800s) it’s a small concentration of consumers in a geographically circumscribed area.

Next Munger moves on to his second and third principles: numerical fluency and thinking in reverse.

“We will next use numerical fluency to ascertain what our target implies. We can guess reasonably that by 2034 there will be about eight billion beverage consumers in the world. On average, each of these consumers will be much more prosperous in real terms than the average consumer of 1884. Each consumer is composed mostly of water and must ingest about sixty-four ounces of water per day. This is eight, eight-ounce servings. Thus, if our new beverage, and other imitative beverages in our new market, can flavor and otherwise improve only twenty-five percent of ingested water worldwide, and we can occupy half of the new world market, we can sell 2.92 trillion eight-ounce servings in 2034. And if we can then net four cents per serving, we will earn $117 billion. This will be enough, if our business is still growing at a good rate, to make it easily worth $2 trillion.”

Munger continues:

“A big question, of course, is whether four cents per serving is a reasonable profit target for 2034. And the answer is yes if we can create a beverage with strong universal appeal. One hundred fifty years is a long time. The dollar, like the Roman drachma, will almost surely suffer monetary depreciation. Concurrently, real purchasing power of the average beverage consumer in the world will go way up. His proclivity to inexpensively improve his experience while ingesting water will go up considerably faster. Meanwhile, as technology improves, the cost of our simple product, in units of constant purchasing power, will go down. All four factors will work together in favor of our four-cent-per-serving profit target. Worldwide beverage-purchasing power in dollars will probably multiply by a factor of at least forty over 150 years. Thinking in reverse, this makes our profit-per-serving target, under 1884 conditions, a mere on fortieth of four cents or one tenth of a cent per serving. This is an easy-to-exceed target as we start out if our new product has universal appeal.”

In this section, Munger demonstrates the value of the basic math involved in a TAM (total addressable market) analysis as part of formulating a thesis for a business. Then he goes on to look at the basic cost structure of the business and ensures that the back-of-the-envelope math makes sense for him to reach his ultimate goal.

As part of this analysis he makes a lot of forward looking predictions with the benefit of hindsight (the depreciation of the dollar, the real purchasing power of the average consumer, worldwide beverage purchasing power etc.) but for now we can ignore those issues.

Munger continues on to the meat of his talk: the subject of creating a product compelling enough to be consumed daily by millions of people. This is where he’s going to bring out his fourth and fifth principles: the value of academic wisdom, and the forces that must be brought together to produce “lollapalooza” effects.

“We must next solve the problem of invention to create universal appeal. There are two intertwined challenges of large scale: First, over 150 years, we must cause a new-beverage market to assimilate about one-fourth of the world’s water ingestion. Second, we must so operate that half the new market is ours while all of our competitors combined are left to share the remaining half. These results are lollapalooza results. Accordingly we must attack our problem by causing every favorable factor we can think of to work for us. Plainly, only a powerful combination of many factors is likely to cause the lollapalooza consequences we desire. Fortunately, the solution to these intertwined problems turns out to be fairly easy if one has stayed awake in all the freshman [college] courses.

Let us start by exploring the consequences of our simplifying “no-brainer” decision that we must rely on a strong trademark. This conclusion automatically leads to an understanding of the essence of our business in proper elementary academic terms. We can see from the introductory course in psychology that, in essence, we are going into the business of creating and maintaining conditioned reflexes. The “Coca-Cola” trade name and trade dress will act as the stimuli, and the purchase and ingestion of our beverage will be the desired responses.

And how does one create and maintain conditioned reflexes? Well, the psychology text gives two answers: (1) by operant conditioning and (2) by classical conditioning, often called Pavlovian conditioning to honor the great Russian scientist. And, since we want a lollapalooza result, we must use both conditioning techniques – and all we can invent to enhance effects from each technique.”

Let’s take some time to define a few of the things that Munger is talking about here so that it’s easy to follow the rest of the argument. Munger is mostly interested in the psychology of consumer decision-making: how can we influence consumers to buy a lot of a certain type of product?

There are two that he’s going to talk about here: operant conditioning and classical conditioning.

Classical conditioning is the method by which a strong innate response can become invoked by a neutral stimulus.

The most famous demonstration of classical conditioning is the work the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov did with dogs: he conditioned dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell.

To do this, every time Pavlov fed his dogs he would ring a bell. After repeating this procedure a few times, Pavlov found that he could ring his bell and the dogs would salivate without any food being present! (It’s historically questionable whether Pavlov actually used a bell, but we’ll leave it in for simplicity.)

Getting back to the subject at hand, it’s probably clear why this concept is so powerful: it means that it’s possible to trigger an innate biological response with a stimulus of your choice. Like, for example, a logo.

Now let’s briefly talk about operant conditioning. B. F. Skinner, the famed Harvard behaviorist describes operant conditioning in this way:

“When a bit of behavior is followed by a certain kind of consequence, it is more likely to occur again, and a consequence having this effect is called a reinforcer.”

In case this is confusing, Skinner elaborates with an example:

“Food, for example, is a reinforcer to a hungry organism; anything the organism does that is followed by the receipt of food is more likely to be done again whenever the organism is hungry.”

There is also a distinction between different types of reinforcers: some are negative and some are positive:

“Some stimuli are called negative reinforcers; any response which reduces the intensity of such a stimulus – or ends it – is more likely to be emitted when the stimulus recurs. Thus, if a person escapes from a hot sun when he moves under cover, he is more likely to move under cover when the sun is again hot. The reduction in temperature reinforces the behavior it is ‘contingent upon’ – that is, the behavior it follows. Operant conditioning also occurs when a person simply avoids a hot sun – when, roughly speaking, he escapes from the threat of a hot sun.”

Now that we have a little bit more background, let’s get back to Munger. Right now he’s trying to figure out how to use operant conditioning to increase the consumption of his product:

“The operant conditioning part of our problem is easy to solve. We need only (1) maximize rewards of our beverage’s ingestion and (2) minimize possibilities that desired reflexes, once created by us, will be extinguished through operant conditioning by proprietors of competing products.

For operant conditioning rewards, there are only a few categories we will find practical:

(1) Food value in calories or other inputs;

(2) Flavor, texture, and aroma acting as stimuli to consumption under neural preprogramming of man through Darwinian natutal selection;

(3) Stimulus, as by sugar or caffeine;

(4) Cooling effect when man is too hot or warming effect when man is too cool.

Wanting a lollapalooza result, we will naturally include rewards in all the categories.

To start out, it is easy to decide to design our beverage for consumption cold. There is much less opportunity, without ingesting beverage, to counteract excessive heat, compared with excessive cold. Moreover, with excessive heat, much liquid must be consumed, and the reverse is not true. It also easy to decide to include both sugar and caffeine. After all, tea, coffee, and lemonade are already widely consumed. And, it is also clear that we must be fanatic about determining, through trial and error, flavor and other characteristics that will maximize human pleasure while taking in the sugared water and caffeine we will provide. And, to counteract possibilities that desired operant-conditioned reflexes, once created by us, will be extinguished by operant-conditioning-employing competing products, there is also an obvious answer: We will make it a permanent obsession in our company that our beverage, as fast as practicable, will at all times be available everywhere throughout the world. After all, a competing product, if it is never tried, can’t act as a reward creating a conflicting habit. Every spouse knows that.”

After talking through operant conditioning, Munger turns to classical conditioning:

“We must next consider the Pavlovian [classical] conditioning we must also use. In Pavlovian conditioning, powerful effects come from mere association. The neural system of Pavlov’s dog causes it to salivate at the bell it can’t eat. And the brain of man yearns for the type of beverage held by the pretty woman he can’t have. And so, Glotz, we must use every sort of decent, honorable Pavlovian conditioning we can think of. For as long as we are in business, our beverage and its promotion must be associated in consumer minds with all other things consumers like or admire.

Such extensive Pavlovian conditioning will cost a lot of money, particularly for advertising. We will spend big money as far ahead as we can imagine. But the money will be effectively spent. As we expand fast in our new beverage market, our competitors will face gross disadvantages of scale in buying advertising to create the Pavlovian conditioning they need. And this outcome, along with other volume-creates-power-effects, should help us gain and hold at least fifty percent of the new market everywhere. Indeed, provided buyers are scattered, our highest volumes will give us very extreme cost advantages in distribution.

Moreover, Pavlovian effects from mere association will help us choose the flavor, texture, and color of our new beverage. Considering Pavlovian effects, we will have wisely chosen the exotic and expensive-sounding name “Coca-Cola,” instead of a pedestrian name like “Glotz’s sugared, caffeinated water.” For similar Pavlovian reasons, it will be wise to have our beverage look pretty much like wine, instead of sugared water. And so we will artificially color our beverage if it comes out clear. And we will carbonate our water, making our product seem like champagne, or some other expensive beverage, while also making its flavor better and imitation harder to arrange for competing products. And, because we are going to attach so many expensive psychological effects to our flavor, that flavor should be different from any other standard flavor so that we maximize difficulties for competitors and give no accidental same-flavor benefit to any existing product.”

Having dealt with Pavlovian conditioning, Munger moves on to social proof:

“What else, from the psychology textbook, can help our new business? Well, there is that powerful ‘monkey-see, monkey-do’ aspect of human nature that psychologists often call ‘social proof.’ Social proof, imitative consumption triggered by mere sight of consumption, will not only help induce trial of our beverage. It will also bolster perceived rewards from consumption. We will always take this powerful social-proof factor into account as we design advertising and sales promotion and as we forego present profit to enhance present and future consumption. More than with most other products, increased selling power will come from each increase in sales.

We can now see, Glotz, that by combining (1) much Pavlovian conditioning, (2) powerful social-proof effects, and (3) wonderful-tasting, energy-giving, stimulating and desirably-cold beverage that causes much operant conditioning, we are going to get sales that speed up for a long time by reason of the huge mixture of factors we have chosen. Therefore, we are going to start something like an autocatalytic reaction in chemistry, precisely the sort of multi-factor-triggered lollapalooza effect we need.

The logistics and the distribution strategy of our business will be simple. There are only two practical ways to sell our beverage: (1) as a syrup to fountains and restaurants, and (2) as a complete carbonated-water product in containers. Wanting lollapalooza results, we will naturally do it both ways. And, wanting huge Pavlovian and social-proof effects we will always spend on advertising and sales promotion, per serving, over 40 percent of the fountain price for syrup needed to make the serving.

A few syrup-making plants can serve the world. However, to avoid needless shipping of mere space and water, we will need many bottling plants scattered over the world. We will maximize profits if (like early General Electric with light bulbs) we always set the first-sale price, either (1) for fountain syrup, or (2) for any container of our complete product. The best way to arrange this desirable profit-maximizing control is to make any independent bottler we need a subcontractor, not a vendee of syrup, and certainly not a vendee of syrup under a perpetual franchise specifying a syrup price frozen forever at its starting level.

Being unable to get a patent or copyright on our super important flavor, we will work obsessively to keep our formula secret. We will make a big hoopla over our secrecy, which will enhance Pavlovian effects. Eventually food-chemical engineering will advance so that our flavor can be copied with near exactitude. But, by that time, we will be so far ahead, with such strong trademarks and complete, “always available” worldwide distribution, that good flavor copying won’t bar us from our objective. Moreover, the advances in food chemistry that help competitors will almost surely be accompanied by technological advances that will help us, including refrigeration, better transportation, and, for dieters, ability to insert a sugar taste without inserting sugar’s calories. Also, there will be related beverage opportunities we will seize.

This brings us to a final reality check for our business plan. We will, once more, think in reverse like Jacobi. What must we avoid because we don’t want it? Four answers seem clear:

First, we must avoid the protective, cloying, stop-consumption effects of aftertaste that are a standard part of physiology, developed through Darwinian evolution to enhance the replication of man’s genes by forcing a generally helpful moderation on the gene carrier. To serve our ends, on hot days a consumer must be able to drink container after container of our product with almost no impediment from aftertaste. We will find a wonderful no-aftertaste flavor by trial and error and will thereby solve this problem.

Second, we must avoid ever losing even half of our powerful trademarked name. It will cost us mightily, for instance, if our sloppiness should ever allow sale of any other kind of “cola,” for instance, a “peppy cola.” If there is ever a “peppy cola,” we will be the proprietor of the brand.

Third, with so much success coming, we must avoid bad effects from envy, given a prominent place in the Ten Commandments because envy is so much a part of human nature. The best way to avoid envy, recognized by Aristotle, is to plainly deserve the success we get. We will be fanatic about product quality, quality of product presentation, and reasonableness of prices, considering the harmless pleasure it will provide.

Fourth, after our trademarked flavor dominates our new market, we must avoid making any huge and sudden change in our flavor. Even if a new flavor performs better in blind taste tests, changing to that new flavor would be a foolish thing to do. This follows because, under such conditions, our old flavor will be so entrenched in consumer preference by psychological effects that a big flavor change would do us little good. And it would do immense harm by triggering in consumers the standard deprival super-reaction syndrome that makes “take-aways” so hard to get in any type of negotiation and helps make most gamblers so irrational. Moreover, such a large flavor change would allow a competitor, by copying our old flavor, to take advantage of both (1) the hostile consumer super-reaction to deprival and (2) the huge love of our original flavor created by our previous work.

Well, that is my solution to my own problem of turning $2 million into $2 trillion, even after paying out billions of dollars in dividends. I think it would have won with Glotz in 1884 and should convince you more than you expected at the outset. After all, the correct strategies are clear after being related to elementary academic ideas brought into play by the helpful notions.”

During the rest of the piece, Munger discusses the parallels between his fictional business plan and Coca-Cola’s actual business (hint: they’re pretty much the same.) He then goes on to relate his story to the main purpose of the talk: our failure to use basic academic wisdom to make better decisions.

He chalks this up, in part, to a failure of academia to produce a useful synthesis of topics like psychology and behavioral economics. He thinks that academic departments are too narrowly focused, and the research of academics to circumscribed.

Is there bullshit to sniff out here?

If you scan the shelves at an airport bookstore, you’re likely to find lots of books that, like Munger’s talk, purport to unveil some of the key attributes of successful companies. If you’ve ever been tempted to pick up a copy of Think Like Zuck: The Five Business Secrets of Facebook’s Improbably Brilliant CEO Mark Zuckerberg you know what I mean.

Because this is a common trope in the business literature – and it’s one that we often swallow uncritically – I want to take a few paragraphs to instill in you a healthy dose of skepticism in any person that purports to unveil the hidden attributes of successful companies:

First, anything that attempts to reduce the success of a business to a few key principles misses out on the obscene complexity that underlies the growth of any kind of organization.

Second, it misses the fact that many (but not all) organizations are incentivized to hide the real story behind their growth in order to protect their image, their investors, their employees, or their (perceived or real) competitive advantages.

Third, these attributes are subject to interpretation via the halo effect: they are seen as good ONLY because the company is successful. Many times you’ll see a CEO characterized as a visionary perfectionist when the stock is up, and an micro-managing egoist when the stock is down.

Fourth, Munger’s talk is (knowingly) given with the benefit of hindsight. It’s easy to point to many of these things as sure signs of success – once the success has been achieved.

Fifth, the attributes you see are subject to selection bias: people generally only write books or give talks about successful companies. Just because a successful company has attribute A, doesn’t mean that there aren’t a thousand other companies with attribute A that went to the graveyard.

What we’re really looking for is evidence that a particular company attribute played a causational role in their success – rather than just merely being associated with that success.

This is incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to do.

In the case of Munger’s talk I’m going to err on the side of believing him for two reasons:

- He puts his money where his mouth is. His very long investment track record provides some demonstration that his framework works at picking companies.

- He doesn’t claim universal applicability. His goal isn’t to give you a foolproof way of predicting company success – it’s to give you a framework, based in basic ideas, to help you think about that success.

So assuming we trust Munger, the next question we have to ask ourselves is: can we use what he’s saying?

Is all of this useful?

Clearly, if you’re running a big company this kind of framework could help you make better decisions. For example, had the executives at Coke who decided to introduce “New Coke” understood conditioning better they might have scrapped the plan before it became a disaster.

Similarly, if you’re an institutional investor evaluating a large consumer business like Coke he provides you an interesting framework to think about.

I think the argument can also be made that it provides a good framework for early-stage technology investors to think about – one that agrees with the startup-focused investors like Paul Graham, Peter Thiel, and others. (I think it’s always interesting when people who come from different backgrounds and work on different problems come to the similar conclusions about something, it usually means that there’s some truth to what they’re saying.)

Applying Munger’s framework to technology investing

If I had to summarize Munger’s advice in a few sentences (with the benefit of reading lots of other articles from him) it would be something like the following:

In order to get large (lollapalooza) effects like rapid growth you need to harness lots of different types of elementary forces. The forces to focus on create what we call positive feedback loops: they’re self-reinforcing. A causes B, B causes more A, which causes more B.

The forces of this type that Munger cites are psychological: operant conditioning and classical conditioning. All companies have to harness these kinds of psychological forces to grow. But there are other ones to look for as well:

- Economies of scale: the larger you are, the cheaper it is to produce your product, the more products you sell, the larger you get

- Network effects: the larger the network becomes, the more valuable the network is, the larger the network gets

- Word of mouth: the more of your product you sell, the more people talk about you, the more of your product you sell

- Big data effects: the more data a search engine has the, the better search results it can return, the more data it gets

- Incumbent advantages: the more large customers you have, the easier it gets to sign large customers, the more large customers you get

Finding companies that harness these effects is important for technology investors because the venture investment model is predicated upon huge returns from companies that dominate large winner-take-all markets.

And how do you get a winner-take all market?

One company has to be able to build an ever-increasing advantage against its competitors. It needs to be able to achieve high enough velocity to escape the gravity of market competition.

But how do you build this kind of ever-increasing lead?

You effectively harness the self-reinforcing forces we’ve been discussing: conditioning, economies of scale, network effects, word of mouth, big data effects, and others.

But what if you’re not an investor. What if you’re thinking of starting your own company? Can you use these ideas to come up with a startup?

Is this generative?

The first question to ask about his framework is this: is it generative?

By this I mean, will it help me generate new ideas for businesses to start. The answer to this question is clearly: no.

Thinking to yourself, “What companies can I start that will have self-reinforcing feedback loops?” doesn’t make your brain generate new ideas. As always, the best way to generate these ideas is through experience.

Paul Graham writes, “The way to get startup ideas is not to try to think of startup ideas. It’s to look for problems, preferably problems you have yourself.”

Ok, so Munger’s framework isn’t generative. The next question we have to ask ourselves is: is it diagnostic? In other words, assuming that Munger has identified some key causational elements of successful companies, how valuable is it for helping us diagnose companies at the idea stage?

The answer to this question is: if you’re looking to build a billion dollar company, it’s at best a marginally helpful guide. And the fact that it’s not incredibly helpful isn’t really Munger’s fault. There’s just no framework of elements out there that would allow us to perfectly predict how well our ideas are going to turn out.

There are lots of reasons for this. Here are a couple:

- Success is stochastic not deterministic

- Execution is more important than mere idea

- Your initial idea of what you’re building is often much different than what you actually build

Because what you actually build is often much different than what you think you’re building at the beginning, exact analysis of this kind is difficult to do. At best, what it can help you with is a general “sniff” test:

In general, does my vision for this product seem like it has the potential to harness some of these forces?

If the answer is yes then it’s time to get on to the next step and build the damn thing.

–

Works Cited:

Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger, Expanded Third Edition, Charlie Munger

Beyond Freedom and Dignity, B.F. Skinner

Recent Posts